UNDP'S ONLINE COURSE ON ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCIES

UNDP'S ONLINE COURSE ON ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCIES

- For further information please visit the additional resource

- For further information please visit the additional resource

- For further information please visit the additional resource

- For further information please visit the additional resource

- For further information please visit the additional resource

- For further information please visit the additional resource

- E-LEARNING HUB

- HOME

- MODULE 1

- LESSON 1

- 13. Background information

- 14. Background

- 15. Background Information

- 16. Background Information

- 17. Background Information

- 18. Background Information

- 19. Background Information

- 20. Background Information

Background information

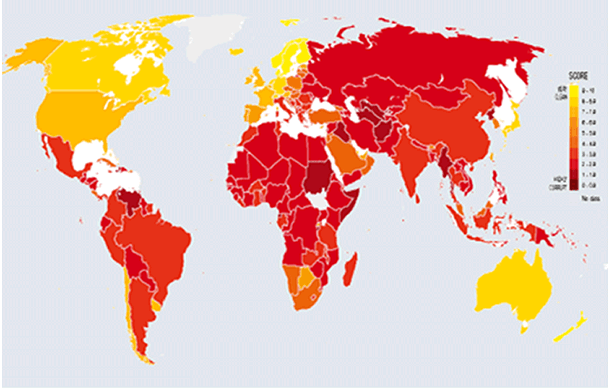

For many years, the establishment of specialized anti-corruption agencies, institutions and bodies (hereafter “referred to as anti-corruption agencies” or “ACAs”) has widely been considered among the most important international initiatives to effectively tackle corruption.

This belief was largely popularized by Singapore’s Corrupt Practice Investigation Bureau (established in 1952) and of Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (established in 1974). Both institutions were widely considered to be effective in reducing corruption in their countries.

During the 1990s and 2000s, specialized anti-corruption agencies were established in many countries. At the same time, countries explored ways to integrate anti-corruption functions into existing institutions, such as Ombudsman and Audit Offices.

Background

Despite the increasing prevalence of national ACAs, these agencies have often been criticized for not living up to their promise of effectively tackling corruption. While many ACAs have been supported by multilateral and bilateral donors over the years as part of the good governance agenda, empirical evidence suggests that most ACAs have had limited impact. Disappointed by the perceived lack of impact in reducing the incidence of corruption, members of the public as well as development partners have increasingly questioned the value of ACAs.

Background Information

UNDP recognizes that many ACAs are not living up to their promise. Nonetheless, the UNDP believes that they can and should play an important role in a country’s national accountability framework, and should receive assistance to do so. This commitment has been reinforced by States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), who say that ACAs are a crucial element of any national anti-corruption framework. Articles 5, 6 and 36 all recognize the need for States Parties to ensure ACAs that have what they need to effectively fulfill their mandates.

Background Information

The 2008 UNDP Practice Note on “Mainstreaming Anti-corruption in Development” explicitly identifies support for ACAs as a major entry point for UNDP’s efforts to support the fight against corruption. The Practice Note draws on UNDP’s experiences in providing technical support to ACAs around the world, highlighting that the capacity of ACAs is at the heart of their failure to meaningfully address corruption at the national level.

Background Information

UNDP has increased resources for capacity development support for ACAs. In 2010, for instance, UNDP directly supported numerous anti-corruption institutions in all regions, helping them develop their capacity to monitor delivery of services by government institutions, to conduct UNCAC self-assessments, to investigate cases of corruption and to increase the coordination mechanism among government institutions, media and civil society in the fight against corruption.

Background Information

To better calibrate UNDP’s assistance to ACAs in the Eastern European and CIS regions, Asia Pacific and the Arab regions, UNDP has conducted specific capacity assessments as a first step towards developing effective and targeted capacity development programs for those ACAs. Drawing on UNDP’s previous ACA capacity assessments, in 2008 the UNDP Bratislava Regional Center developed a Methodology for Assessing Capacities of anti-corruption agencies to Perform Preventive Functions.

This course expands that initial methodology to include enforcement functions as well, drawing on experiences and lessons learned from the field, including capacity assessments from Bhutan, Mongolia, Montenegro, Kosovo, Turkey, Moldova and the FYR of Macedonia and other countries.

Background Information

In line with UNCAC, the course covers the assessment of both:

(i) preventive functions (Article 69) and

(ii) law enforcement functions (Article 36).

Accordingly, the course has been designed to focus on functions performed by an agency, rather than the particular institutional arrangement or name of the agency. It also takes a modular approach, whereby key capacity issues are captured in individual “modules”, which can then be applied depending on which functions are relevant to the specific agency being reviewed.

Background Information

It is important to keep in mind that a capacity assessment is only the first step in a longer process of developing and implementing a capacity development plan.

The assessment phase is critical to capacity development efforts because it lays the foundations for the design and implementation of informed, appropriate, and effective capacity development responses. It can also set the baseline for continuous monitoring and evaluation of progress, and thereby lay a solid foundation for long-term planning and implementation, with sustainable results from capacity development interventions.

It is important that ACAs, the governments that establish them, and the development partners that support them stay focused on the main goal: To develop effective and sustainable national capacities to address corruption and thereby improve the lives of citizens.